Food focused —> perspective on the future

– – – –

Our future table is likely to be shaped by many factors, from diminishing resources and growing human populations to increased self-awareness of the impact food has on health to cultural phenomena like food fetishism, culinary hedonism and ritual.

For a sense of what we will not be eating, perhaps we can look to the advice of the past 100 years and see where that has gotten us.

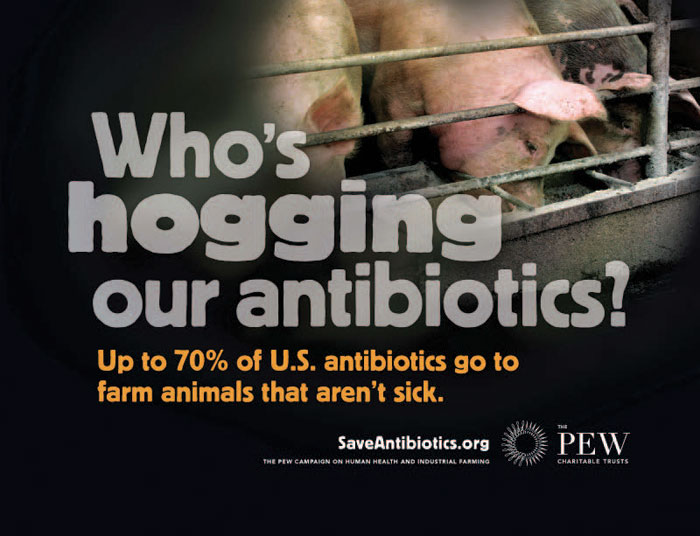

In the 1930s, the chemical company DuPont adopted the (paraphrased) slogan “Better living through chemistry,” and in many ways this idea has loomed large over the evolution of food and foodlike substances in the past century: From Crisco to canned cheese, we’ve forsaken real food for convenience. There is no question in my mind that our relationship with food has been severely derailed in recent years, and I think it’s not illogical to draw a connection between this derailment and the rise of modern disease and the decline of natural resources on our planet.

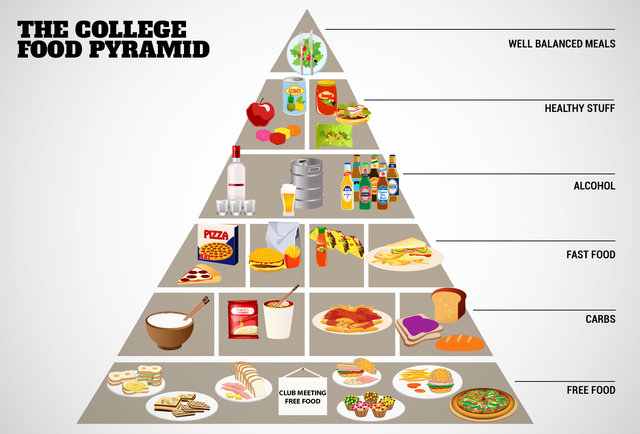

As the average body mass in the developed world has grown consistently over the past century, and the rates of autoimmune diseases, type-2 diabetes and other modern diseases have gone up, our relationship with food seems to have become much more antagonistic. Many of us look at culinary indulgences as corporal sins that must be neutralized through physical penitence. My Saturday pizza binge must be zeroed out with 45 minutes of looping my legs through imaginary figure-eights on an elliptical trainer, plugged deeply into the frenetic chyron of CNN, until a digital ticker tells me that I’ve paid my dues for yesterday’s pleasure.

I remember clearly, 25 years ago when I first visited Spain, being shocked that there were so few grocery stores and so many markets. The fish at the markets came from nearby waters, the produce from the surrounding countryside. On recent visits to Spain I have noticed a much greater proliferation of large, “box” grocery stores and far more fast-food chains. While the markets still appear to be as busy as I recall, the people who patronize them seem to be split into two camps: older women shopping for produce, and everyone else taking photos of food and updating their social media status.

This fetishistic obsession with food is evident in the ever-increasing number of celebrity chefs and food-related television shows, websites and blogs. All of the attention being paid, however, doesn’t seem to be alleviating the real corporal and environmental crises we are experiencing as byproducts of our highly developed modern food systems. In fact, in the past 25 years the rates of obesity in Spain have more than doubled, with childhood obesity and chronic illness also on the rise. Anecdotally, it would appear that the rise of chronic illness has gone hand in hand with the fall of traditional cooking.

What will that mean for us in 35 years? Our bodies and our planet can only sustain so much abuse. Unless we’re resigned to living longer, sicker lives, something’s got to give.

To take a stab at guessing what we might be eating, we need to think about all the things that are affected by how we eat. I often forget that I’m not an individual, but rather part of a complex community — a community of cells, muscle fibers, bacteria, nervous systems and bones. I am also part of a greater community, a family, a circle of friends, a group of colleagues, a neighborhood, a vibrant city, a unique planet. The way I eat has a direct impact on all of these communities, some more explicitly than others, but each community is affected by the choices I make about the food that goes in my mouth.

For as long as we have been social creatures, food has been at the heart of any community. In the most basic of terms, we formed bands, tribes, villages and cities to increase our chances of survival, initially to hunt and gather and later to cultivate and distribute food.