For America’s craft beer revolution, brewing battle has come to a head

The independent beer movement has exploded, threatening Big Beer and posing new dilemmas for ambitious craft brewers.

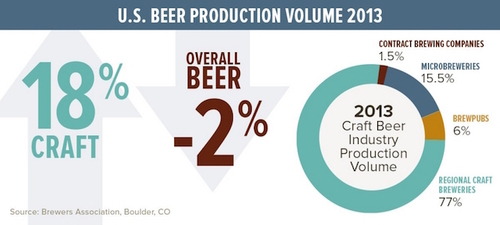

A troubling milestone for Big Beer came in 2013, when craft brew snuck past Budweiser — the once-dominant “King of Beers” — in number of barrels shipped, by 16.1 to 16 million. Compare that to 2003, when Budweiser shipped almost 30 million barrels to craft’s 5 million, and the trajectory is clear.

“At Anheuser-Busch, you see a future where if you don’t act now to restructure the marketplace, your present product selection is going to confine you to a much smaller business down the road,” said Barry Lynn, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation who has done extensive research on the beer market.

So restructuring the marketplace is what Big Beer has begun to do, experts say. Contrary to its recent anti-craft messaging, Anheuser-Busch currently owns a handful of craft breweries itself, starting with the 2011 purchase of Goose Island in Chicago. It has since bought out Blue Point, 10 Barrel, and, last year, Elysian in Washington. The company has not commented whether the buying spree will continue, including in an email to Al Jazeera, but its strategy so far seems to involve subsidizing and selling its craft offerings cheaper than its competitors, proliferating them across its massive, coordinated distribution networks.

Lynn said he didn’t think the plan was to profit off these beers directly. “What they want to be able to do is offer wholesalers or retailers a full array of products, to say ‘you don’t need to go anywhere else, we’ve got your craft covered.’”

That’s what the Brewers Association, which represents the craft beer industry, fears. Paul Gatza, the association’s director, said the Big Two can, by way of co-opted distributors, offer preferential treatment – prices and promotional displays, for example – to bars and stores who choose not to carry independent brews. Now that craft is in their repertoire, Gatza said, “you’ll see it more and more at bars, where Anheuser-Busch is dominating the facility and all the beers on tap are produced or owned by them.“

In some states, Big Beer has taken the even more aggressive strategy of buying out wholesale distributors, which move alcohol from the brewers themselves to retailers. In doing so, Big Beer is challenging the formalized 3-tier system that has regulated the alcohol market in the U.S since the 1930s — whereby the brewer or distiller, wholesale distributor and retailer are all supposed to be separate entities, or tiers. Established in the aftermath of prohibition, the idea was that an intentionally inefficient system would keep the alcohol industry’s once-formidable political power in check. Decades later, those safeguards against vertical integration helped catalyze the craft revolution.

Small brewers argue that the acquisitions should be illegal, pointing out there is no incentive for a distributor owned by Anheuser-Busch to carry anyone else’s brew. The controversy has come to a head in a number of states, most recently Kentucky, where earlier this month the House approved a bill backed by independent brewers that could require Anheuser-Busch to sell its distributors in the state.

Damon Williams, director of sales and marketing for Anheuser-Busch in Louisville, Kentucky, told Al Jazeera in an email that the bill "has nothing to do with craft beers and everything to do with greedy special interests.”

But craft brewers in other states say the threat of consolidation is real. In Washington state, a craft mecca where the Big Two once had among the lowest market shares in the country, small brewers like Heather McClung say their options have begun to dwindle since Anheuser-Busch swooped in to buy out distributors.

“At some point there won’t really be any choice left,” said McClung, the co-founder and owner of Schooner Exact in Seattle, and president of the Washington Brewers’ Guild. “And then you become lost in someone’s distributor books, because all these little brands will have to go somewhere.”

Even in states where brewers are prohibited from buying distributors outright, Anheuser-Busch Inbev and SABMiller can exert considerable pressure on wholesalers. Thanks to an unprecedented spate of mergers and acquisitions that have gone mostly unfettered by anti-trust regulators — the “other revolution in beer,” as Lynn termed it — the Big Two now encompass all of the top five name-brand domestic beers: Bud Light, Coors Light, Budweiser, Miller Light and Natural Light. Most wholesalers can’t afford to lose their business, even if consumers are demanding more interesting, complex flavors of craft.

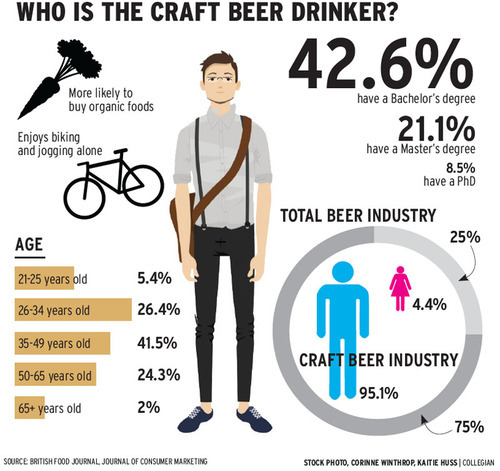

Compounded pressure from above and a widening ground floor have left small brewers with difficult choices to make. Selling out to the Big Two remains fraught with risks for brands like Goose Island, not to mention frowned upon by craft purists. “Some say it doesn’t feel as good when your money isn’t going to a small, local company anymore,” said Gatza of the Brewers Association.

A more palatable option for ambitious craft breweries, analysts say, is to reach out to venture capital firms for help with expansion they can’t achieve on their own. But even the idea of forging partnerships with profit-maximizing investors — sacrificing the craft industry’s hallmark independence, and perhaps its emphasis on local job creation — makes many brewers uneasy.

“It’s awesome that they’re interested, but there are drawbacks,” said McClung, of Schooner Exact. “More and more people are entering the market because they think there’s a chance to make money, rather than for the true craft brewing ideals.” An influx of inexperienced or undertrained brewers could undermine or dilute the “craft” distinction, she said. “Then our bubble could burst.”

At Bronx Brewery, Brown and Gallant said venture capital was something they’d consider if the circumstances were right. But they also recognized that in today’s increasingly stratified market, being small might not be the worst thing. Big Beer seems to have its sights set on marginalizing or co-opting major craft players, rather than 6,000 barrel-per-year microbreweries like theirs. “The little guys will always have a niche market, even at a higher price point,” Brown said.

“We’ve seen a rather dramatic change in the makeup of the marketplace as a whole, and I don’t envision that changing one way or another,” added Stephen Beaumont, author of the World of Beer blog and two books on beer. The Big Two can leverage their economies of scale to restrict market access, he said, “but they can’t change tastes. To a certain degree they’re grasping, and they have been for some time.”