Climate change: why the Guardian is using a new storyline to detail the threat

Alan Rusbridger – the guardian

As global warming argument moves on to politics and business, Alan Rusbridger of the Guardian explains the thinking behind our major series on the climate crisis.

Climate change is the biggest threat to humanity. Yet journalism has struggled for two decades to tell a story that doesn’t leave the public feeling disheartened and disengaged.

Journalism tends to be a rear-view mirror. We prefer to deal with what has happened, not what lies ahead. We favour what is exceptional and in full view over what is ordinary and hidden.

Famously, as a tribe, we are more interested in the man who bites a dog than the other way round. But even when a dog does plant its teeth in a man, there is at least something new to report, even if it is not very remarkable or important.

There may be other extraordinary and significant things happening – but they may be occurring too slowly or invisibly for the impatient tick-tock of the newsroom or to snatch the attention of a harassed reader on the way to work.

What is even more complex: there may be things that have yet to happen – stuff that cannot even be described as news on the grounds that news is stuff that has already happened. If it is not yet news – if it is in the realm of prediction, speculation and uncertainty – it is difficult for a news editor to cope with. Not her job.

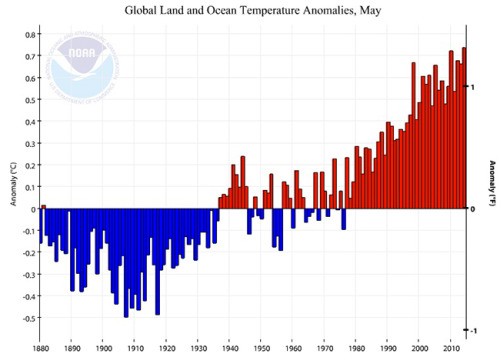

For these, and other, reasons changes to the Earth’s climate rarely make it to the top of the news list. The changes may be happening too fast for human comfort, but they happen too slowly for the newsmakers – and, to be fair, for most readers.

These events that have yet to materialise may dwarf anything journalists have had to cover over the past troubled century. There may be untold catastrophes, famines, floods, droughts, wars, migrations and sufferings just around the corner. But that is futurology, not news, so it is not going to force itself on any front page any time soon.

Even when the overwhelming majority of scientists wave abig red flag in the air, they tend to be ignored. Is this new warning too similar to the last? Is it all too frightening to contemplate? Is a collective shrug of fatalism the only rational response?

The climate threat features very prominently on the home page of the Guardian on Friday even though nothing exceptional happened on this day. It will be there again next week and the week after. You will, I hope, be reading a lot about our climate over the coming weeks.

One reason for this is personal. This summer I am stepping down after 20 years of editing the Guardian. Over Christmas I tried to anticipate whether I would have any regrets once I no longer had the leadership of this extraordinary agent of reporting, argument, investigation, questioning and advocacy.

Very few regrets, I thought, except this one: that we had not done justice to this huge, overshadowing, overwhelming issue of how climate change will probably, within the lifetime of our children, cause untold havoc and stress to our species.

So, in the time left to me as editor, I thought I would try to harness the Guardian’s best resources to describe what is happening and what – if we do nothing – is almost certain to occur, a future that one distinguished scientist has termed as “incompatible with any reasonable characterisation of an organised, equitable and civilised global community”.

It is not that the Guardian has not ploughed considerable time, effort, knowledge, talent and money into reporting this story over many years. Four million unique visitors a month now come to the Guardian for our environmental coverage – provided, at its peak, by a team including seven environmental correspondents and editors as well as a team of 28 external specialists.

They, along with our science team, have done a wonderful job of writing about the changes to our atmosphere, oceans, ice caps, forests, food, coral reefs and species.

For the purposes of our coming coverage, we will assume that the scientific consensus about man-made climate change and its likely effects is overwhelming. We will leave the sceptics and deniers to waste their time challenging the science. The mainstream argument has moved on to the politics and economics.

The coming debate is about two things: what governments can do to attempt to regulate, or otherwise stave off, the now predictably terrifying consequences of global warming beyond 2C by the end of the century. And how we can prevent the states and corporations which own the planet’s remaining reserves of coal, gas and oil from ever being allowed to dig most of it up. We need to keep them in the ground.

There are three really simple numbers which explain this (and if you have even more appetite for the subject, read the excellent July 2012 Rolling Stone piece by the author and campaigner Bill McKibben, which – building on the work of the Carbon Tracker Initiative – first spelled them out).

2C: There is overwhelming agreement – from governments, corporations, NGOs, banks, scientists, you name it – that a rise in temperatures of more than 2C by the end of the century would lead to disastrous consequences for any kind of recognised global order.

565 gigatons: “Scientists estimate that humans can pour roughly 565 more gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere by mid-century and still have some reasonable hope of staying below 2C,” is how McKibben crisply puts it. Few dispute that this idea of a global “carbon budget” is broadly right.

2,795 gigatons: This is the amount of carbon dioxide that if they were burned would be released from the proven reserves of fossil fuel – ie the fuel we are planning to extract and use.

You do not need much of a grasp of maths to work out the implications. There are trillions of dollars worth of fossil fuels currently underground which, for our safety, simply cannot be extracted and burned. All else is up for debate: that much is not.

We need to keep it in the ground. This was the starting point for the group of journalists who met early in January to start considering how we would cover the issue.

Some will make the case for governmental action. Within nine months, the nations of the world will assemble in Paris, as they did previously in Copenhagen and Kyoto and numerous other summits now forgotten. Can they find the right actions and words, where they have failed before? It is certainly important that they feel the pressure to achieve real change.

Others will make the case for reducing the fossil fuel exposure of investment portfolios by decarbonisation. Or going further to full divestment from the most polluting fossil fuel extraction companies. Next week, McKibben will describe how the cause of divestment is moving rapidly from a fringe campaign to a mainstream concern for banks and fund managers.

It is now very much on the radar of the financial director rather than the social responsibility department. If most of these reserves are unburnable, they are asking, then what does that say about the true value of carbon-dependent companies? It is a question of fiduciary responsibility as much as a moral imperative.

We will look at who is getting the subsidies and who is doing the lobbying. We will name the worst polluters and find out who still funds them. We will urge enlightened trusts, investment specialists, universities, pension funds and businesses to take their money away from the companies posing the biggest risk to us. And, because people are rightly bound to ask, we will report on how the Guardian Media Group itself is getting to grips with the issues.

In addition to words, images and films, we will be podcasting the series as we go along, to give some insight and transparency about our reporting and how we are framing and developing it.

We begin on Friday and on Monday with two extracts from the introduction to Naomi Klein’s recent book, This Changes Everything. This has been chosen because it combines sweep, science, politics, economics, urgency and humanity. Antony Gormley, who has taken a deep interest in the climate threat, has contributed two artworks from his collection that have not been exhibited before – the first of many artists with whom we hope to collaborate over coming weeks.

Where does this leave you? I hope not feeling impotent and fearful.

Some of you may be marching in London on Saturday 7 March. As McKibben will argue next week, the fight for change is also full of opportunity and optimism. And we hope that many readers will find inspiration in our series to make their own contribution by applying pressure on their workplace, or pension fund, to move.

But, most of all, please read what we write. Real change can only follow from citizens informing themselves and applying pressure. To quote McKibben: “This fight, as it took me too long to figure out, was never going to be settled on the grounds of justice or reason. We won the argument, but that didn’t matter: like most fights it was, and is, about power.”