Regional future – Know your food: Mexico farm hardship, bounty for US tables

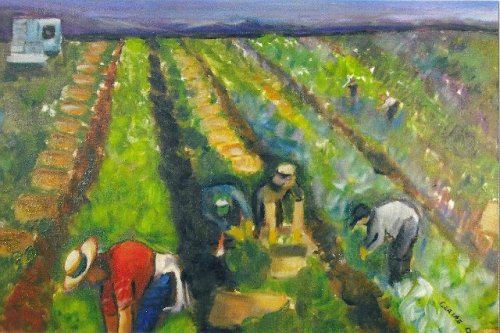

An LA Times reporter and photographer find that thousands of laborers at Mexico’s mega-farms endure harsh conditions and exploitation while supplying produce for American consumers.

The tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers arrive year-round by the ton, with peel-off stickers proclaiming “Product of Mexico.”

Farm exports to the U.S. from Mexico have tripled to $7.6 billion in the last decade, enriching agribusinesses, distributors and retailers.

American consumers get all the salsa, squash and melons they can eat at affordable prices. And top U.S. brands — Wal-Mart, Whole Foods, Subway and Safeway, among many others — profit from produce they have come to depend on.

These corporations say their Mexican suppliers have committed to decent treatment and living conditions for workers.

But a Los Angeles Times investigation found that for thousands of farm laborers south of the border, the export boom is a story of exploitation and extreme hardship.

Many farm laborers are essentially trapped for months at a time in rat-infested camps, often without beds and sometimes without functioning toilets or a reliable water supply. Some camp bosses illegally withhold wages to prevent workers from leaving during peak harvest periods.

Laborers often go deep in debt paying inflated prices for necessities at company stores. Some are reduced to scavenging for food when their credit is cut off. It’s common for laborers to head home penniless at the end of a harvest.

Those who seek to escape their debts and miserable living conditions have to contend with guards, barbed-wire fences and sometimes threats of violence from camp supervisors.

Major U.S. companies have done little to enforce social responsibility guidelines that call for basic worker protections such as clean housing and fair pay practices.

The farm laborers are mostly indigenous people from Mexico’s poorest regions. Bused hundreds of miles to vast agricultural complexes, they work six days a week for the equivalent of $8 to $12 a day.

The squalid camps where they live, sometimes sleeping on scraps of cardboard on concrete floors, are operated by the same agribusinesses that employ advanced growing techniques and sanitary measures in their fields and greenhouses.

The contrast between the treatment of produce and of people is stark.

In immaculate greenhouses, laborers are ordered to use hand sanitizers and schooled in how to pamper the produce. They’re required to keep their fingernails carefully trimmed so the fruit will arrive unblemished in U.S. supermarkets.

“They want us to take such great care of the tomatoes, but they don’t take care of us,” said Japolina Jaimez, a field hand at Rene Produce, a grower of tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers in the northwestern state of Sinaloa. “Look at how we live.”

He pointed to co-workers and their children, bathing in an irrigation canal because the camp’s showers had no water that day.

At the mega-farms that supply major American retailers, child labor has been largely eradicated. But on many small and mid-sized farms, children still work the fields, picking chiles, tomatillos and other produce, some of which makes its way to the U.S. through middlemen. About 100,000 children younger than 14 pick crops for pay, according to the Mexican government’s most recent estimate.

Pedro Vasquez, working the chile pepper fields near Leon, Guanajuato, is one of the estimated 100,000 Mexican children younger than 14 who pick crops for pay, according to the government’s most recent estimate. He is 9 years old.

During The Times’ 18-month investigation, a reporter and a photographer traveled across nine Mexican states, observing conditions at farm labor camps and interviewing hundreds of workers.

At half the 30 camps they visited, laborers were in effect prevented from leaving because their wages were being withheld or they owed money to the company store, or both.

Some of the worst camps were linked to companies that have been lauded by government and industry groups. Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto presented at least two of them with “exporter of the year” honors.

The Times traced produce from fields to U.S. supermarket shelves using Mexican government export data, food safety reports from independent auditors, California pesticide surveys that identify the origin of imported produce, and numerous interviews with company officials and industry experts.

The practice of withholding wages, although barred by Mexican law, persists, especially for workers recruited from indigenous areas, according to government officials and a2010 report by the federal Secretariat of Social Development. These laborers typically work under three-month contracts and are not paid until the end. The law says they must be paid weekly.

The Times visited five big export farms where wages were being withheld. Each employed hundreds of workers.

Wal-Mart, the world’s largest retailer, bought produce directly or through middlemen from at least three of those farms, The Times found.

Bosses at one of Mexico’s biggest growers, Bioparques de Occidente in the state of Jalisco, not only withheld wages but kept hundreds of workers in a labor camp against their will and beat some who tried to escape, according to laborers and Mexican authorities.

Asked about its ties to Bioparques and other farms where workers were exploited, Wal-Mart released this statement:

“We care about the men and women in our supply chain, and recognize that challenges remain in this industry. We know the world is a big place. While our standards and audits make things better around the world, we won’t catch every instance when people do things that are wrong.”